History of Photography

Early 19th Century to Late 20th Century

Mid 1820s

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce was experimenting using a camera obscura, a box with a hole in one side that projects an image of its surroundings onto a surface inside a darkened space. He used a piece of bitumen dissolved in lavender oil and coated a sheet of pewter with the paste. He placed the sheet in the camera obscura and let the light hit it for 8 hrs. He used lavender oil to remove any unexposed bitumen and what was left made the image you see here. It was a building, a barn, and a tree, which looks a little bit odd. That is because of the light and shadows. Since it took 8 hrs to gather light, the sun moved across the sky removing any shadows and making it all sunlit.

1829-1839

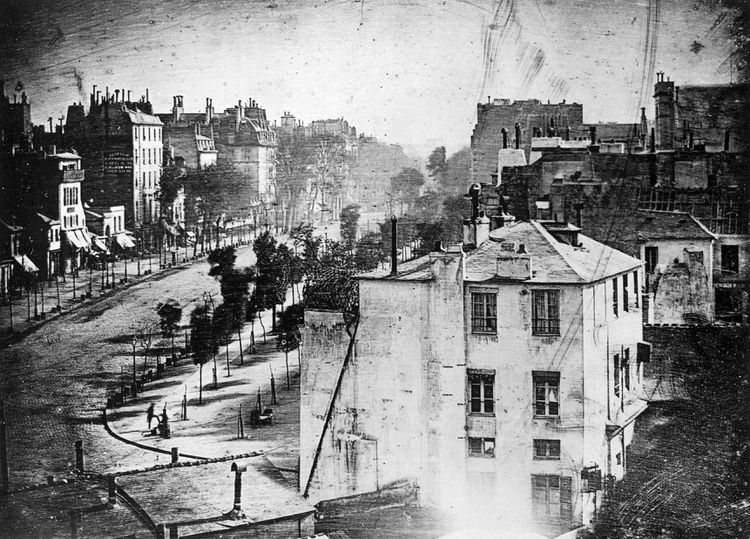

Niépce formed a partnership with Louis Daguerre to enhance the photographic process he had developed, and they collaborated until Niépce's passing in 1833. Following Niépce's death, Daguerre continued to refine the technique, ultimately creating a new process that, while rooted in their initial discoveries, significantly diverged from Niépce's original work. He named this innovation the Daguerreotype, in his own honor. In 1839, he and Niépce’s son transferred the rights to the daguerreotype to the French government and published a booklet detailing the process. Daguerre successfully reduced the exposure time to under 30 minutes and ensured the permanence of the image, marking the beginning of the modern photography era.

Late 1830s

From its inception, photography played a crucial role in journalism. Shortly after the French government's announcement of the daguerreotype process in 1839, publications began featuring woodcuts or lithographs credited as “from a daguerreotype.” This 1847 daguerreotype is believed to be the first photograph captured for news purposes, illustrating a man being arrested in France. The image was allegedly featured in a historical account of the 1848 Revolution titled "Journées illustrées de la révolution de 1848." Early instances of photojournalism were seen during the Crimean War (1853–1856) and the American Civil War (1861–1865), with notable photographers such as Roger Fenton and Mathew Brady documenting the stark realities of war and its consequences. These images, often published as engravings, offered the public a new, realistic insight into contemporary events. By the late 19th century, technological innovations like halftone printing enabled the direct reproduction of photographs in newspapers and magazines, establishing photojournalism as an essential medium for narrative and influencing public perception of global events.

1840s

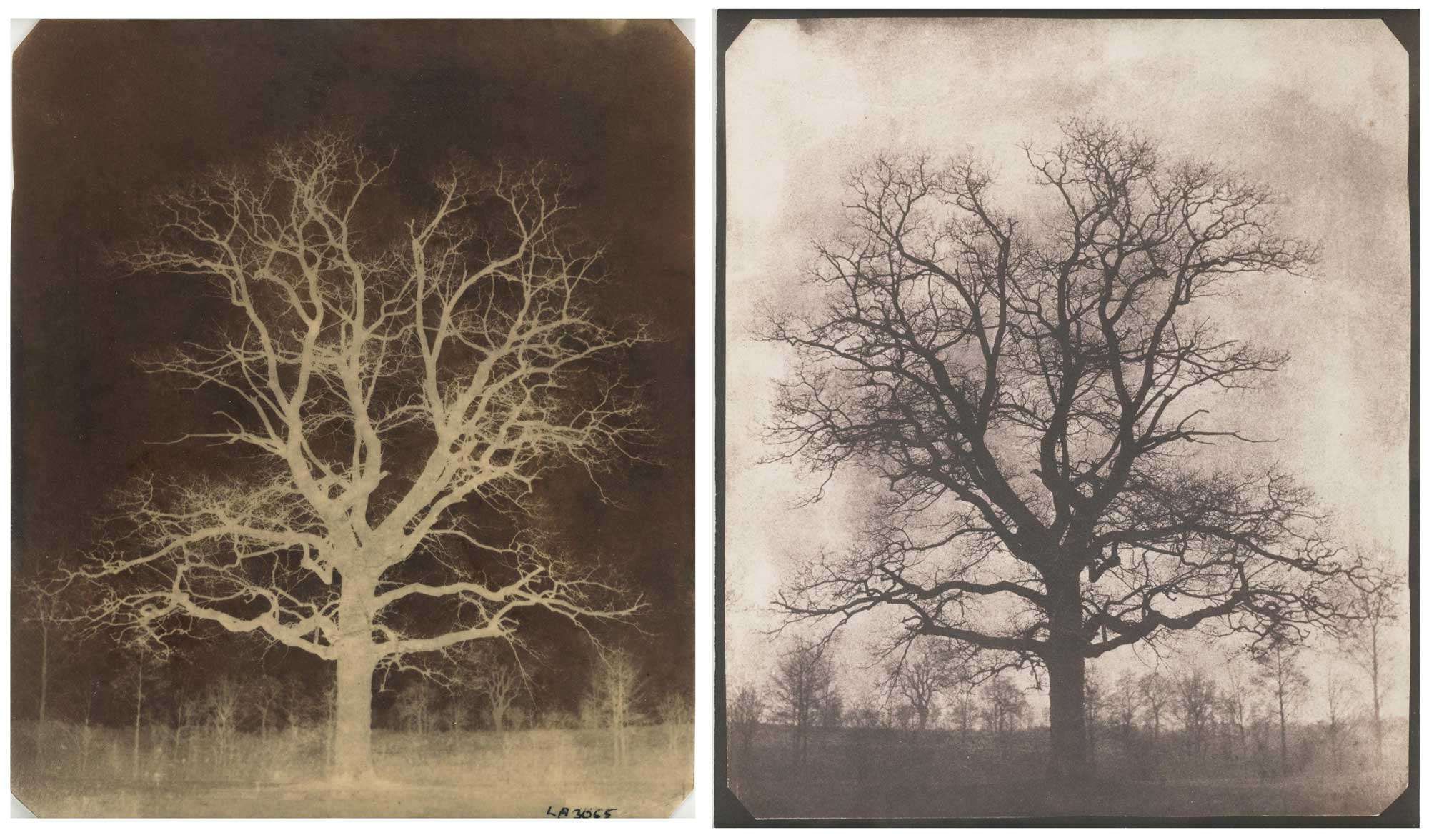

The calotype, developed by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1841, was among the earliest photographic methods to employ a negative-positive system, laying the groundwork for contemporary photography. This process entailed applying a layer of silver iodide to a sheet of paper to form a light-sensitive surface. Following exposure in a camera, the paper was processed with gallic acid, yielding a visible negative image. This negative could subsequently be utilized to generate multiple positive prints through contact printing onto another sensitized paper sheet.

1850s

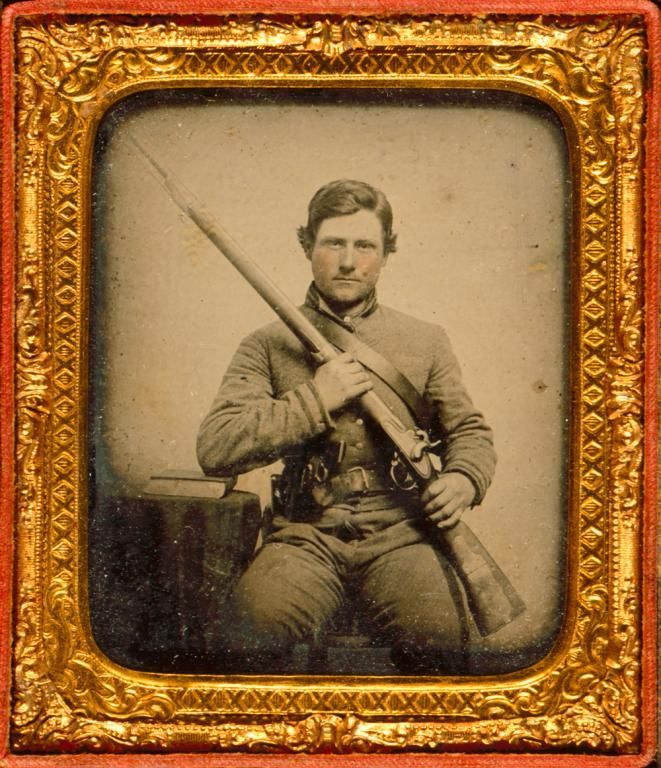

The popularity of the daguerreotype started to decline in the1850s with the introduction of the wet collodion process.The procedure involves coating, sensitizing, exposing, and developing the photographic material within approximately fifteen minutes, which necessitates the use of a portable darkroom in the field. The collodion process which facilitated the emergence of the ambrotype—a quicker and more cost-effective photographic method. James Ambrose Cutting patented the ambrotype process in 1854, and it reached its peak popularity from the mid-1850s to the mid-1860s. An ambrotype consists of an underexposed glass negative placed against a dark background, which produces a positive image. Photographers frequently enhanced the surface of the plate with pigments to introduce color, typically tinting cheeks and lips red and adding gold highlights to jewelry, buttons, and belt buckles.

1853

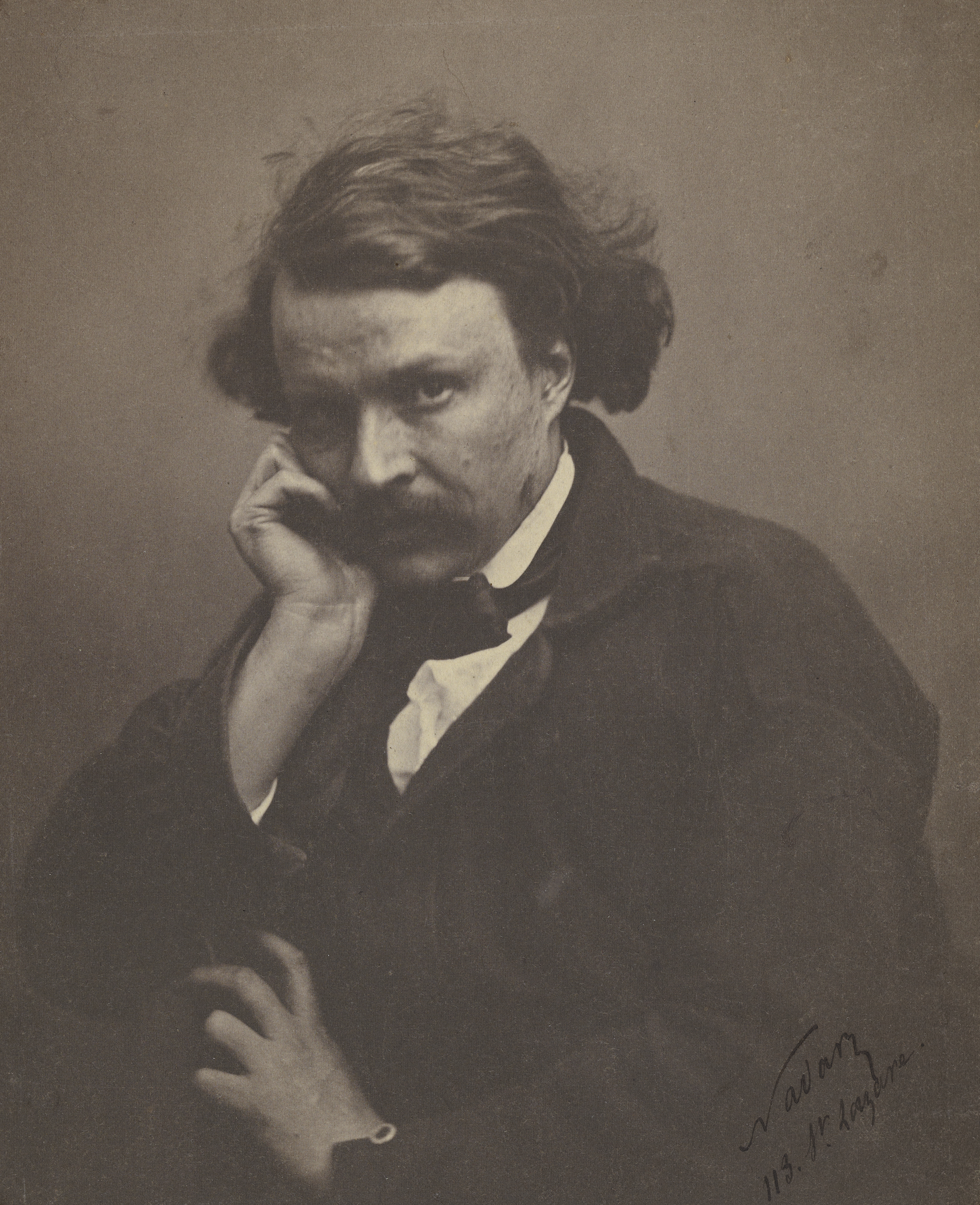

Félix Nadar, born in 1820 in Paris, transformed 19th-century photography and aerial imaging. Initially starting his career as a caricaturist and writer, Nadar eventually found his true calling in photography in 1853. His innovative approach and technical skill quickly positioned him as a trailblazer in the field. Nadar's portraits captured the essence of the Parisian cultural elite, immortalizing prominent figures such as Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, and Sarah Bernhardt with remarkable intimacy and depth. His work was often lauded for the profound connection he established with his subjects. Renowned for his exceptional lighting techniques, Nadar created striking shadows around his models, a feat made possible through the collodion glass process pioneered by Frederic Scott Archer. As one of the early adopters of this groundbreaking technology, he produced distinctive images. His studio became a vibrant center for artists and intellectuals, notably hosting the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874.

1853

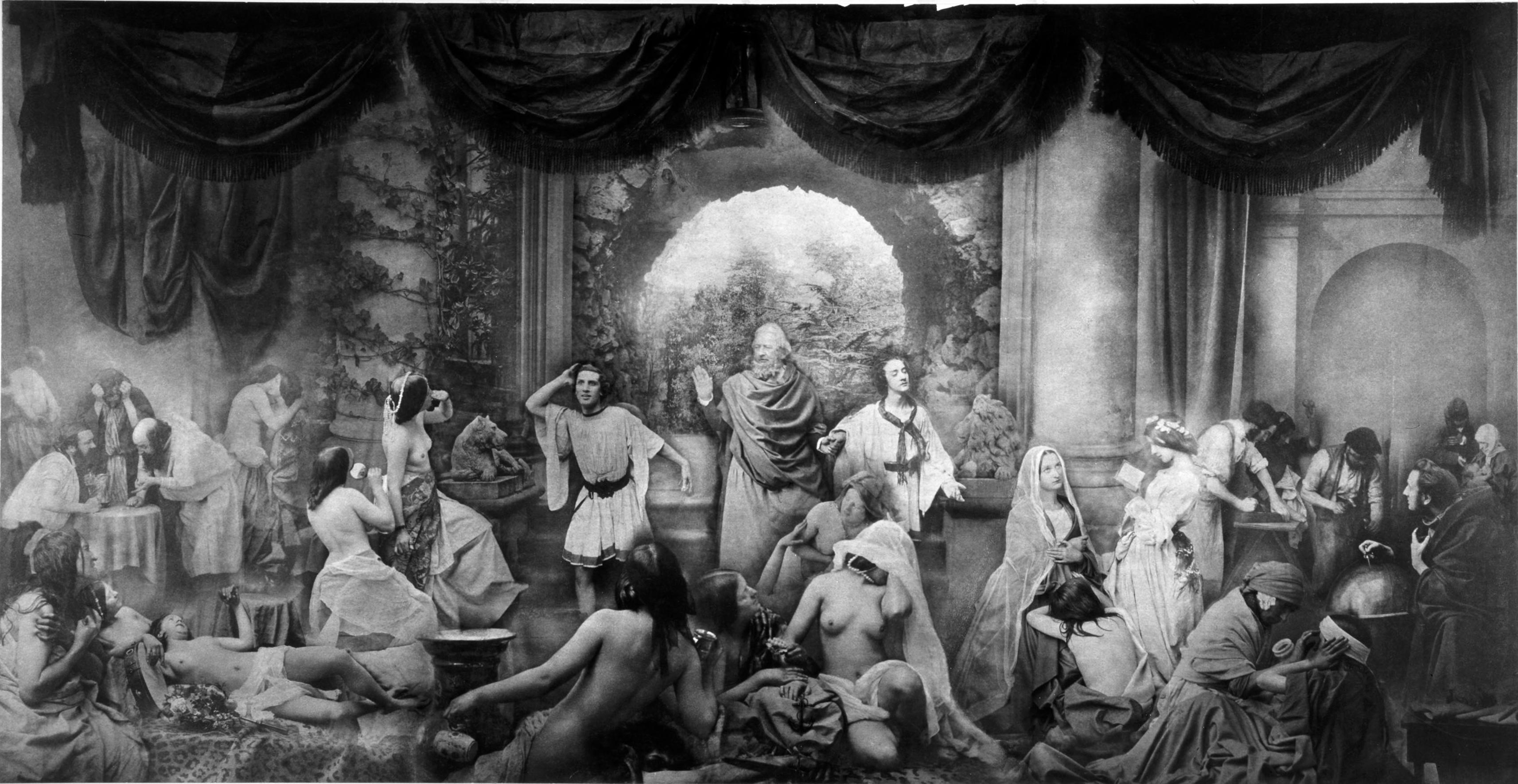

In the mid-19th century, the establishment of photographic societies, such as the Photographic Society in London (1853) and the Société Française de Photographie in Paris (1854), signified a pivotal shift towards acknowledging photography as an aesthetic art form. These organizations, alongside various journals, advocated for the appreciation of both general photography and its artistic merits. To counter the perception of photography as a purely mechanical process, photographers like O.G. Rejlander crafted intricate compositions by merging multiple negatives. Rejlander's distinguished work, The Two Ways of Life (1857), employed 30 negatives to illustrate an allegorical narrative, showcasing the artistic potential of photography. His groundbreaking methods garnered acclaim, with the photograph exhibited at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition and subsequently acquired by Queen Victoria, underscoring the rising prominence of photography within the art community.

Late 1850s

Between the late 1850s and the 1870s, British photographers played a significant role in documenting the natural landscapes and monuments within the empire. Notable figures include Francis Frith, who created three albums of well-composed images in Egypt and Asia Minor; Samuel Bourne, who captured various scenes across India; John Thomson, who provided a descriptive account of life and landscapes in China; and French photographer Maxime Du Camp, who accompanied Gustave Flaubert on a government commission to document Egyptian landscapes and monuments. The photographs of historical buildings and sites served multiple purposes, including satisfying antiquarian interests, providing restoration information, supplying artists with reference material for their paintings, and supporting preservation initiatives.

1864

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) was a groundbreaking British photographer celebrated for her evocative and artistic portraits. Beginning her photography journey in 1864, she distinguished herself with her innovative techniques, including soft focus, dramatic lighting, and emotional depth, which challenged the rigid conventions of Victorian photography. Her subjects ranged from notable figures like Charles Darwin and Alfred Lord Tennyson to friends and family, often portrayed in allegorical or literary-inspired contexts. Cameron regarded photography as a form of art rather than mere documentation, aiming to capture the essence and character of her subjects. Although her unconventional methods, such as intentional blurriness and tight framing, faced criticism during her lifetime, they were later recognized for their expressive and modern qualities. Cameron's work significantly shaped the evolution of portrait photography, fostering a more creative and intimate approach to conveying human emotion.

1870s

In the 1870s, numerous efforts were undertaken to discover a dry alternative to wet collodion, enabling the preparation of plates in advance and their development long after exposure, thus removing the necessity for a portable darkroom. In 1871, Richard Leach Maddox, an English physician, proposed the suspension of silver bromide in a gelatin emulsion, a concept that culminated in 1878 with the launch of factory-manufactured dry plates coated with gelatin containing silver salts. This development signified the dawn of the modern photography era.

1978

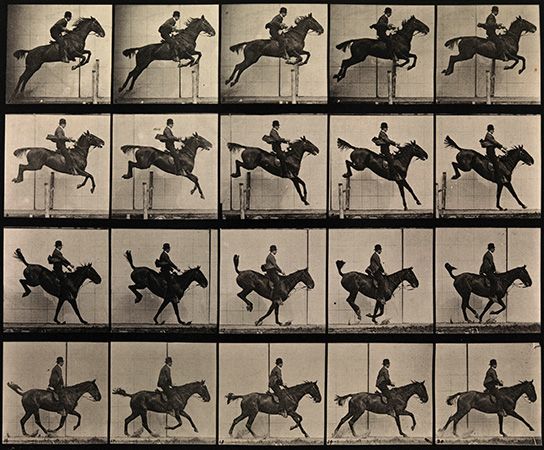

Several years prior to the advent of the dry plate process, Eadweard Muybridge captivated audiences worldwide with his remarkable photographs of horses captured in California. To achieve these images, Muybridge employed a series of 12 to 24 cameras strategically positioned side by side in front of a reflecting screen at Stanford’s Palo Alto track on June 19, 1878. The cameras were triggered by threads that were broken as the horse raced past, allowing Muybridge to capture a series of sequential images depicting various stages of the horse's walk, trot, and gallop. The international publication of these photographs in both popular and scientific media revealed that the positions of the horse's legs were distinct from those depicted in conventional hand-drawn illustrations.

Late 1800s

Documentary photography emerged in the late-19th century as a means to visually document and convey the realities of life, often highlighting social issues and historical events. Pioneers such as John Thomson and Jacob Riis utilized this medium to illuminate societal inequalities, including poverty and urban living conditions. The introduction of portable cameras and advancements in photographic techniques, such as wet plate collodion and roll film, facilitated the capture of spontaneous and candid moments. The genre gained significant traction during the Great Depression, with organizations like the Farm Security Administration (FSA) commissioning photographers such as Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans to portray the hardships faced by rural Americans. This form of photography emphasized narrative through striking visual stories, with the intent to inform, foster empathy, and inspire social change. It established the groundwork for contemporary photojournalism and continues to serve as a vital instrument for advocacy and the preservation of history.

1880s

Gelatin plates exhibited approximately 60 times the sensitivity of collodion plates, enabling the use of handheld cameras rather than requiring a tripod. In the late 1880s, George Eastman developed a flexible, unbreakable film base that could be rolled. The emulsion applied to a cellulose nitrate film base, like Eastman's, facilitated the mass production of box cameras. The Kodak camera, launched by George Eastman in 1888, became particularly popular due to its user-friendly design, which significantly promoted the growth of amateur photography, particularly among women, who were the focus of much of Kodak's marketing efforts. Instead of glass plates, this camera utilized a roll of flexible negative material capable of capturing 100 circular images. In 1889, this was upgraded to film on a transparent nitrocellulose plastic base, a material invented in 1887 by Reverend Hannibal Goodwin from Newark, New Jersey.

1902

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Photo-Secession, established in 1902 by Alfred Stieglitz, emerged as a significant Pictorialist organization in New York City, dedicated to elevating photography to the status of fine art. Drawing inspiration from European avant-garde movements, the group introduced innovative photographic methods such as gum-bichromate and bromoil printing, resulting in painterly and distinctive prints. Through exhibitions held at Stieglitz's gallery, “291,” and the influential journal Camera Work (1903–1917), the Photo-Secession showcased the works of both photographers and modernist artists. As photography evolved to emphasize its intrinsic qualities rather than merely imitating other art forms, the emphasis gradually shifted towards “straight” photography, which prioritized sharp focus and pure tone. This transformation led to the departure of several founding members, while Stieglitz continued to support photographers like Paul Strand, whose powerful, unaltered images captured the evolving artistic perspective of the medium.